Direct Commercial Flights Between Egypt and Sudan Resume After Conflict

Egypt has resumed direct commercial flights to Sudan for the first time since the conflict broke out between rival generals in Sudan nearly five months…

Egypt has resumed direct commercial flights to Sudan for the first time since the conflict broke out between rival generals in Sudan nearly five months…

Adama and Moussa Sarr have lost track of the exact number of days they spent adrift at sea. The brothers found themselves drifting aimlessly somewhere…

Thousands of protesters gathered outside a French military base in Niger’s capital, Niamey, demanding the withdrawal of French troops following a military coup that enjoys…

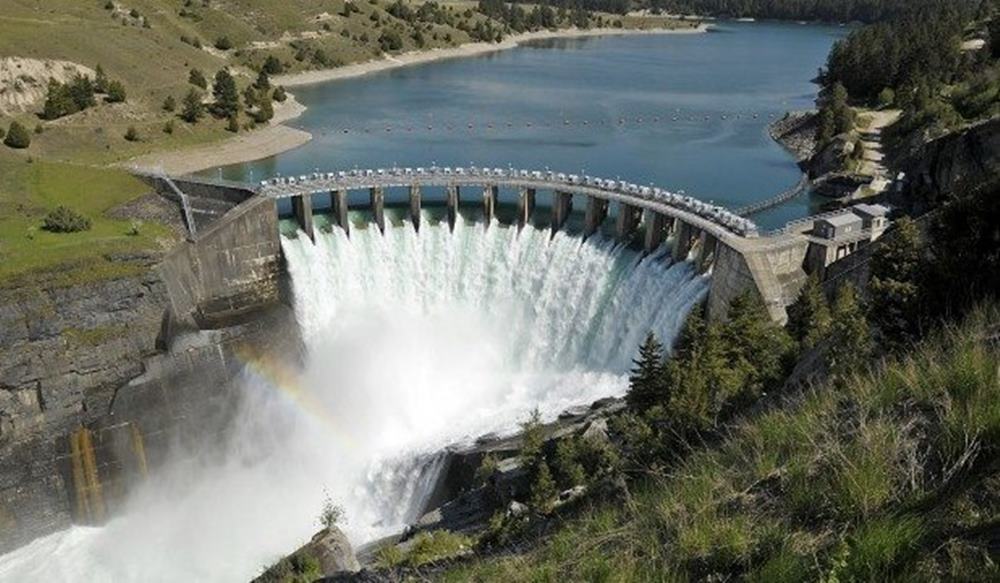

Nigeria’s emergency management agency keeps a close watch on river levels as Cameroon releases water from the Lagdo Dam, urging communities to prepare for potential…

TikTok, the global social media sensation, is making significant strides in Africa with its latest announcement of opening an office in Kenya. This strategic move…

Support the growth of our platform by purchasing our merch.

When artistes submit their music on our website, we encourage their audience to engage with these submissions by using the like or dislike buttons. These ratings play a key role in helping us identify high-quality content that resonates with our listeners. Our dedicated team carefully considers user ratings and preferences, handpicking exceptional submissions for special recognition. The rating system operates through the use of browser cookies, making these ratings unique to individual browser users. This means that each user's likes and dislikes are stored in their browser's cookies, allowing us to gather accurate and personalised feedback. As part of our commitment to supporting talent, we occasionally offer free unbiased airplay to these chosen artistes. This opportunity allows them to reach a wider audience and gain valuable exposure within the music scene. By tapping into the power of our listeners' ratings, we aim to create a community-driven platform that uplifts and celebrates the best in music.